Shifting climate patterns and periods of drought and excessive precipitation appear to becoming increasingly extreme, posing continual challenges such as physical setbacks in the agricultural industry and social challenges associated with extreme weather conditions. In the water industry, we find ourselves simultaneously working toward solutions to conditions of both too little water and too much water. Most recently, precipitation levels trended to be above average across the upper Midwest and Rocky Mountain regions.

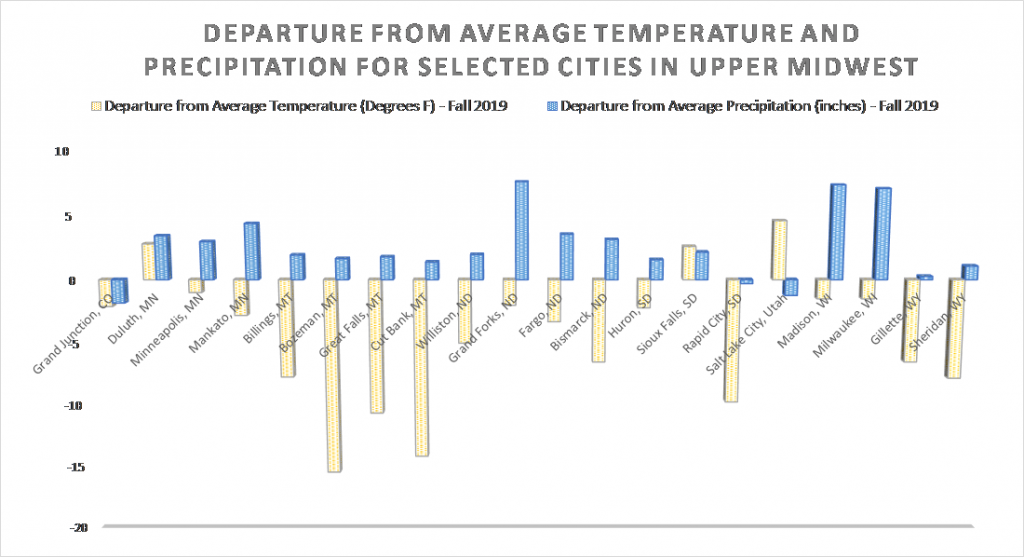

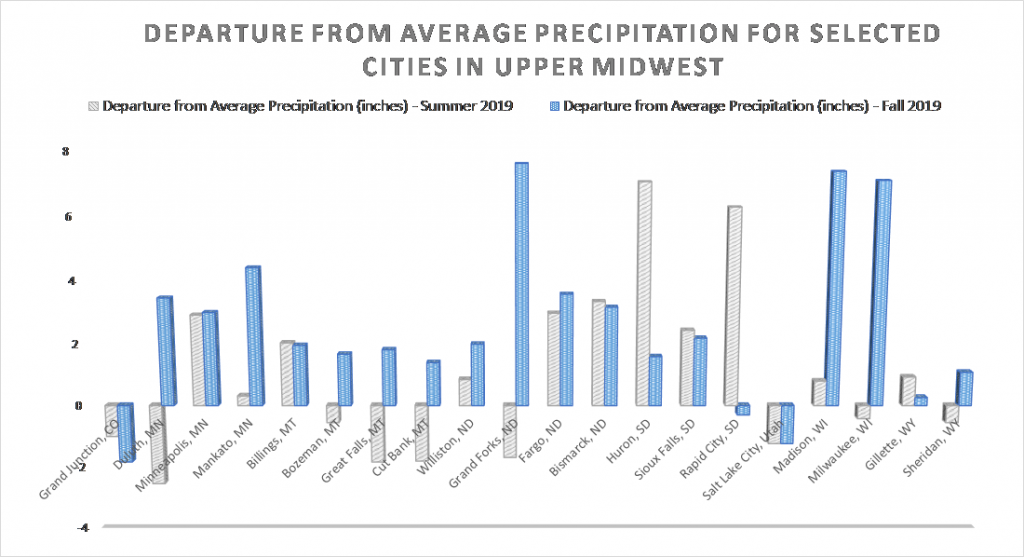

Figure 1 illustrates a comparison between average temperature and total precipitation for the months of September through November 2019 for cities around the region. In general, the average temperatures were below normal, while precipitation was above normal. Figure 2 compares the departure from average precipitation for summer and fall 2019, illustrating how unusually wet this fall was for many cities. Summer precipitation was also above average for many. Most notably, South Dakota experienced unusually high levels of precipitation.

Water supply issues are nothing new. There are many large projects across the region that are working to address current and future water supply shortages. The opposing problem, excessive precipitation, has recently presented challenges to stormwater systems, sanitary sewer collection systems, and wastewater treatment facilities across the region. Between inflow/infiltration (I/I) and foundation/clear water seepage that can end up in the sanitary sewer, wastewater flows can reach 10 to 20 times the average flow during and after major rain events. I/I can create capacity problems at wastewater plants as well as localized portions of the sewer system if sewer mains and lift stations are overloaded. In addition, the treatment of clear water is simply a waste of financial resources.

Most communities in the region prohibit sump pump discharge to floor drains or the connection of foundation drains directly to the sanitary system to eliminate the unnecessary treatment of this clear water. City ordinances generally require sump pump connections that transfer the water outside onto the homeowner’s property. A secondary requirement is typically that sump drainage be directed away in a manner so as not to negatively impact neighboring properties, streets, and sidewalks. In some cases, property owners install piping that directs the drainage to the street and into the sanitary system. Particularly in cities where this is permissible, it is common for City ordinances to allow for the connection of sump pumps to the sanitary sewer from April through October. This reduces hazards related to icy sidewalks and streets, damage to roadways, and additional maintenance associated with ice-plugged storm drains.

An informal survey of communities around the region resulted in the following:

- In Minnesota, it is a violation of State law to discharge drainage from a sump into a municipal sanitary system. The League of Minnesota Cities has developed an example ordinance language that can be accessed at https://www.lmc.org/page/1/I-IModelOrdinance.jsp?ssl=true.

- State law in Iowa requires drainage from sump pumps, foundation drains, and roof drains be directed to the storm sewer or onto the ground, not into the sanitary sewer. As a result, many cities in Iowa appear to be in the midst of a concerted public education effort that includes systematic inspection of all properties.

- In South Dakota, information for some communities indicates the diversion of sump drainage to the sanitary sewer is allowed in the winter months, typically November through March. More than half of the cities for which sump drainage was specified prohibited discharge to the sanitary sewer any time of year. This was noted particularly for those communities that transfer wastewater to a facility operated by a neighboring community and are therefore charged for the entire volume pumped regardless of waste load strength.

- In North Dakota, the results were mixed, with some prohibiting discharge to the sanitary sewer any time of year and several allowing for winter discharge. The cities of Fargo and West Fargo require customers to apply for a variance to discharge to the sanitary sewer October 1 through March 31. The variance carries an annual cost, and the City of Fargo also includes an additional charge on the monthly utility bill for those properties. Random inspections are completed throughout the year. Fargo has prepared an informative sump pump flyer, which can be found at: http://download.cityoffargo.com/0/sump_pump_success_2009.pdf.

- Little information on sump discharge governance was found for Montana, but the available information generally followed that for cities in North and South Dakota.

- Of those communities reporting ordinance language, most did not require completion of an application for the variance. The majority reported that random inspections would be completed, and fines ranging from $50 to $500 per month could be assessed for violations.

Education is the Best Tool

Reducing unnecessary flows to the wastewater treatment system is very important. The challenge associated with regulation of sump discharge is that it is difficult to enforce. Many communities provide very good information on City webpages designed to educate residents why the discharge of clear water into the sanitary sewer is not allowed. Most inspection programs involve random checks followed by a grace period in which to fix any violations, after which a fine would be imposed. Some programs initiate a fine immediately upon identification of a violation. While fines are sometimes an effective incentive, ongoing education may yield the most benefit. Frequently capitalizing on opportunities to highlight the stormwater and sanitary/wastewater systems, such as the importance of minimizing sanitary flows and the implications that practice can have on near-term and long-term capital and financial needs, should be an active strategy to present a compelling argument against the cost burden of directing sump water down the drain.